Introduction

Over the last few years, Transformers have emerged as the de-facto deep learning architecture in modelling language. Their unprecendented success in solving complex language tasks, reasoning (or mimmicking it), solving math and coding problems, have ushered in a new era in AI, powering successful AI products like ChatGPT.

The key innovation of transformers lies in the self-attention mechanism, which allows each tokens in the input sequence to attend to every other token in the sequence.

The self-attention mechanism is a series of transformations that allow transformers introduce information about a token’s context into it’s latent space representation and was introduced in the seminal Transformers paper as Scaled Dot Product Attention.

In the image above, Ideally we expect the self-attention mechanism to create an embedding for the token “flies” that encodes a meaning closer to “the flow of time” in the first sentence, and one that has encodes flies in relation to insects in the second sentence.

In recent times, most of the spotlight in research on self-attention has been on techniques focused on optimizing computational and memory efficiency such as

. However transformers are still notorious

Differential Attention was introduced in a 2024 paper by a team at Microsoft called Differential Transformer that proposes a new transformers architecture. However the only major difference between a differential transformer and a transformer is the differential attention mechanism

Noise in Self Attention.

As mentioned earlier, the goal of self-attention is to include information about a token’s context into it’s embeddings. This is carried out by performing a series of transformations that take the embeddings of all tokens in the input and returns context-aware embeddings that can be thought of as weighted sums of learned representations of all tokens in the input sequence. The weights computed in this process are called attention weights and they represent how much attention is paid to other tokens in the sequence.

Transformers for all of their glory however, are still notorious for paying attention to irrelevant context in a sequence. By visualizing the attention scores of a transformer model during a retrieval task, the authors of differential attention compared the attention maps of transformers to those of differential transformers.

(attention scores visualization)

The key idea behind Differential Attention is a technique called Differential Denoising.

This is a simple process that involves substracting two different attention weights computed from two attention maps. To readers with a background in Electrical Engineering, this might sound familiar to a common denoising electrical component, the Differential Amplifier.

Differential Amplifiers are amplifiers that are mainly used to reduce noise in signals. They amplify the difference between two input signals and remove noise in the process. They key idea behind this is that, if noise exists in a system, then equal amount of noise added to the input signals. If A and B are provided as the inputs to a Differential Amplifier, the differential amplifier amplifies the difference between signal A and B, and rejects( provides low gain) their commmon input (the noise) simply called the common mode.

Differential Denoising also finds application in Noise-Cancellation headphones.

Now that the core idea of removing noise by taking the difference between two signals has been explored, let’s take a look at the inner workings of a differential amplifier.

Differential Attention Architecture

The key difference between Differential attention and self-attention mechanism lies in how their attention weights are computed.

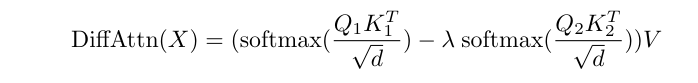

The differential attention mechanism computes outputs using the equation:

\[ \text{DiffAttn}(X) = \left( \text{softmax}\left(\frac{Q_1 K_1^T}{\sqrt{d}}\right) - \lambda \cdot \text{softmax}\left(\frac{Q_2 K_2^T}{\sqrt{d}}\right) \right) V \]where:

- \( Q_1, Q_2 \) are query matrices,

- \( K_1, K_2 \) are key matrices,

- \( V \) is the value matrix,

- \( \lambda \) is a learnable scalar,

- \( d \) is the head dimension.

As a comparison, here’s how self attention computes outputs:

\[ \text{SelfAttn}(X) = \left( \text{softmax}\left(\frac{Q K^T}{\sqrt{d}} \right) \right) \]Implementation

This implementation assumes that the differential attention layer is implemented as a standalone module.

class DiffAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, args: DiffAttnArgs,):

A key detail to pay close attention to is that we set the number of attention heads to half that of a normal transformer model, then proceed to set the dimension of each head to

self.num_heads = args.n_heads # half of transformers head

self.head_dim = args.dim // args.n_heads // 2

This might seem odd, as intuitively, each head usually has a dimension of:

self.head_dim = args.dim // args.n_heads

Taking GPT-2-small as an example, with 12 attention heads and each head having a head dimension of 64. Using differential attention, we would set the number of heads to 6 instead, and have a head dimension of 64 (with 6 heads), when we really should have a head dimension of 128 with 6 heads(following transformer’s convention).

The key, query and vector projection layers are instantiated just like they are in self-attention:

self.wq = nn.Linear(args.embed_dim, args.embed_dim, bias=False)

self.wk = nn.Linear(args.embed_dim, args.embed_dim, bias=False)

self.wv = nn.Linear(args.embed_dim, args.embed_dim, bias=False)

the scaling constant is defined as :

self.scaling = self.head_dim ** -0.5

the same as in self-attention, if you chose to multiply by the numerator (the dot product of key and query vectors).

In order to balance gradient computation with the rest of the model, the lambda value is parameterized as :

\[ \lambda = e^{(\lambda_{q1} \cdot \lambda_{k1})} - e^{(\lambda_{q2} \cdot \lambda_{k2})} + \lambda_{\text{init}} \]where

\[ \lambda_{q1} ,\lambda_{k1}, \lambda_{q2}, \lambda_{q2} \]are learnable vectors and are instantiated as :

self.lambda_q1 = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(self.head_dim, dtype=torch.float32))

self.lambda_q2 = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(self.head_dim, dtype=torch.float32))

self.lambda_k1 = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(self.head_dim, dtype=torch.float32))

self.lambda_k2 = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(self.head_dim, dtype=torch.float32))

is defined as:

def lambda_init_fn(depth):

"""

Function for calculating Lambda_init

Args:

depth (int): Decoder layer index containing the attention mechanism.

Returns:

float: lambda init value.

"""

return 0.8 - 0.6 * math.exp(-0.3 * depth)

where L or depth is the layer index (index of the decoder layer the attention module resides in).

finally:

self.lambda_init = lambda_init_fn(args.depth)

Layer normalization is also initialized using Root-Mean-Square Normalization.

self.sublayer_norm = RMSNorm(2 * self.head_dim, eps=1e-5,)

The forward method is then implemented as follows:

- The key, query and value vectors are computed and split into n_heads for multihead attention.

q = self.wq(x) k = self.wk(x) v = self.wv(x) q = q.view(bsz, tgt_len, 2*self.num_heads, self.head_dim) k = k.view(bsz, tgt_len, 2*self.num_heads, self.head_dim) v = v.view(bsz, tgt_len, self.num_heads, 2*self.head_dim) - Next, Rotary Positional Embeddings are added to the Key and Query vectors to include positional information in the sequence

q,k = apply_rotary_emb(q, k, freqs_cis)

To make up for the halved head_dim, the key and query heads each have twice the number of heads (head_dim should always equal embed_dim / num_heads). The same is done in the value vector however, here we use 2x the head dimension.

Having twice the number of heads for the key and query vector makes it possible to have two attention weights.

The attention scores the same as in self-attention with scaling and a causal masked applied.

q *= self.scaling q = q.transpose(1,2) k = k.transpose(1,2) v = v.transpose(1,2) attn_weights = torch.matmul(q, k.transpose(2,3)) if attn_mask is None: attn_mask = torch.triu( torch.zeros((tgt_len, tgt_len) ).float() .type_as(attn_weights), diagonal= 1+offset ) attn_weights = torch.nan_to_num(attn_weights) attn_weights += attn_maskSoftmax is applied to get the attention weights.

attn_weights = F.softmax(attn_weights, dim=-1, dtype=torch.float32).type_as( attn_weights )\( \lambda \) is calculated as :

lambda_1 = torch.exp( torch.sum( self.lambda_q1 * self.lambda_k1, dim=-1).float()).type_as(q) lambda_2 = torch.exp( torch.sum( self.lambda_q2 * self.lambda_k2, dim=-1).float()).type_as(q) + self.lambda_init lambda_full = lambda_1 - lambda_2

where lambda_1 and lambda_2 are the LHS and RHS of the equation we saw earlier :

\[ \lambda = \exp(\lambda_{q1} \cdot \lambda_{k1}) - \exp(\lambda_{q2} \cdot \lambda_{k2}) + \lambda_{\text{init}} \]Here’s the key part, the attention weights are now halved across the head_dimensions, so the model now has half the number of heads, and two different attention weights in each head.

attn_weights = attn_weights.view( bsz, self.num_heads, 2, tgt_len, src_len)The difference between both attention weights is then:

attn_weights = attn_weights[:, :, 0] - lambda_full * attn_weights[:, :, 1]

Finally the attention weights are multiplied with the value vector to create the new context vectors, RMS norm is applied and the heads are concatenated into one output vector that has dim = embed_dim

ctx_vec= torch.matmul(attn_weights, v) ctx_vec = self.sublayer_norm(ctx_vec) ctx_vec = ctx_vec.transpose(1,2).reshape( bsz, tgt_len, self.num_heads * 2 * self.head_dim)

Conclusion

Differential transformers have demonstrated great potential early on, achieving comparable performances at 65% the size of transformers in language modelling and outpeform transformers on various downstream tasks.